Bareknuckle and the London Prize Ring

The recent spike in the popularity of bareknuckle boxing is a phenomenon fueled, in part, by the growth of MMA. As gloves became smaller for the cage, some people have done away with them entirely, leading to several unsanctioned, yet legal bareknuckle promotions. In the UK, the growth of bareknuckle harks back to the pugilistic past of the island nation, where British boxers were revered for their gameness and heart. Let’s take a look at prizefighting, founded by pioneers like Jack Broughton, and see how modern bareknuckle stacks up against the historic original.

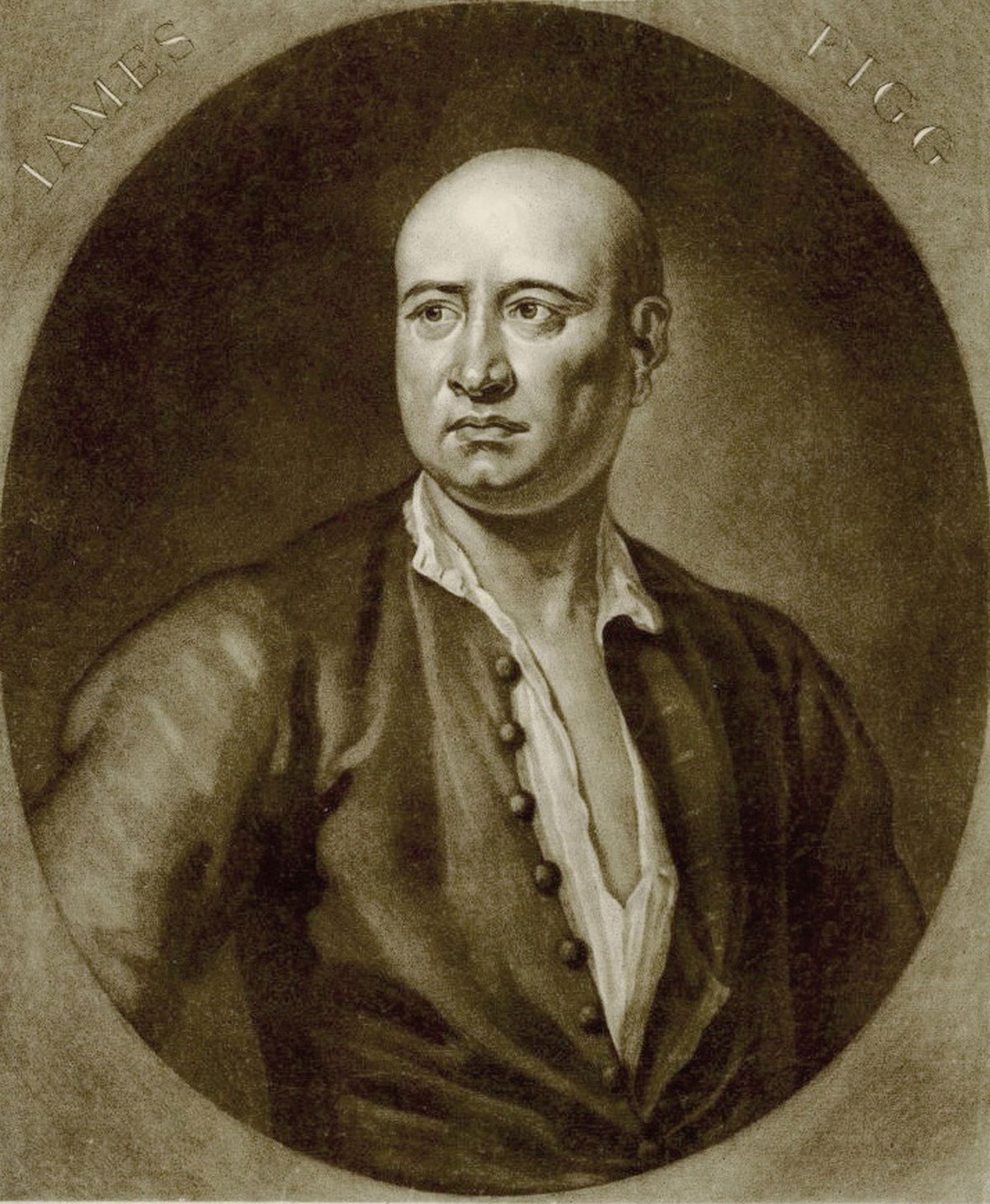

It all started with James Figg. While there had been prizefights for countless years before his rise to fame, Figg, a fencer and pugilist from Thame in Oxfordshire, founded the first school of boxing in 1719. It was his protégé, Jack Broughton, who created the first codified rules for his Amphitheatre on Tottenham Court Road, London in 1743. The Broughton Rules evolved into the London Prize Ring Rules, laid out in 1838 and revised in 1853. The creation of rules and the subsequent revisions were due to in-ring deaths. Broughton banned “butting” and “purring”, which was a slang for kicking a man when he was down. The London Prize Ring Rules added further measures to ensure that pugilists were protected from unscrupulous practices such as kicking, scratching, biting and gouging. The London Prize Ring Rules were slowly replaced by the Marquess of Queensberry Rules. Originally written in 1867 for amateur bouts, these rules mandated fighters wear gloves. Thus began the modern sport as we know it today.

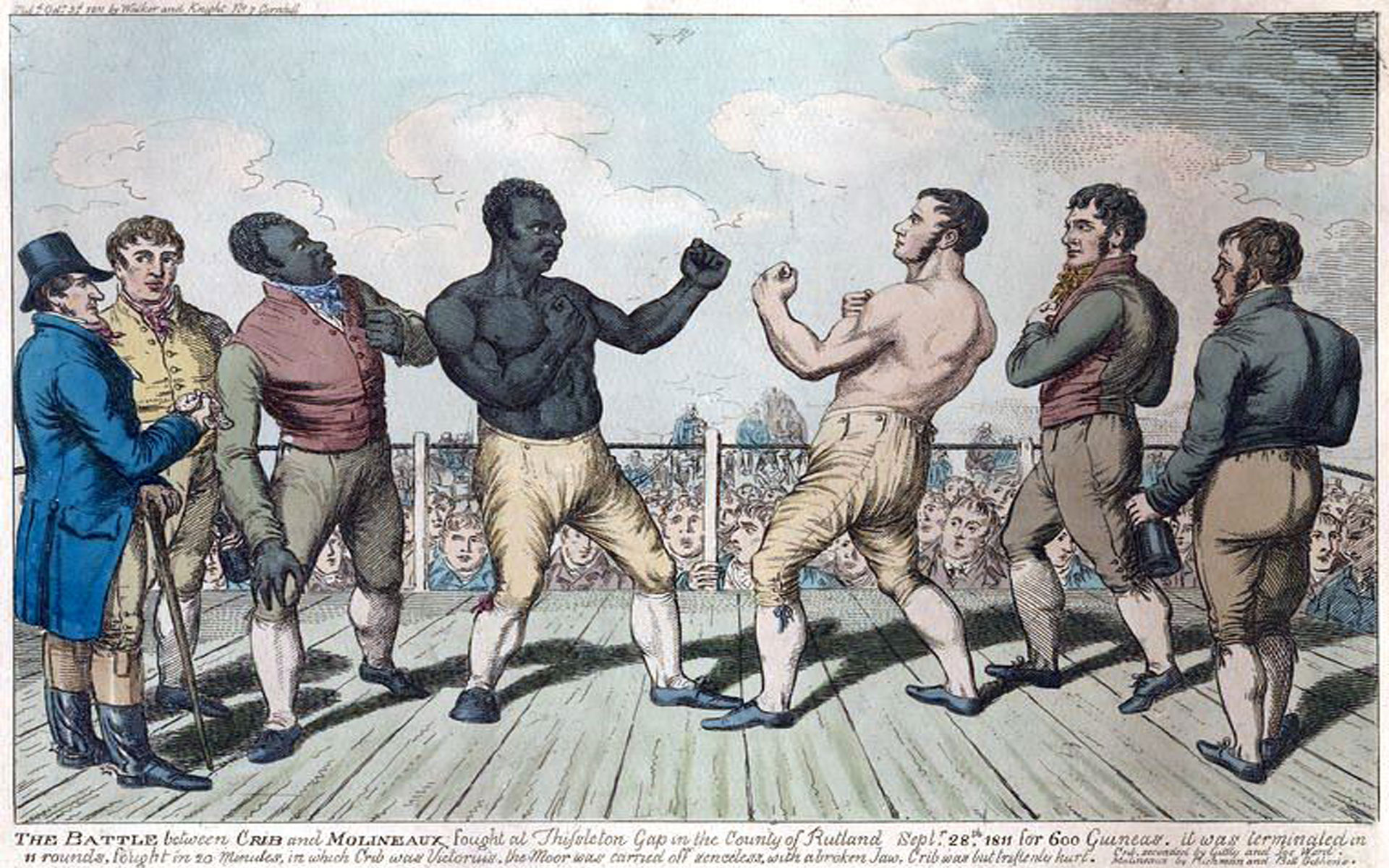

Broughton’s Rules and the London Prize Ring Rules offered a very different version of the boxing we know today. Fights were on turf or on wooden decks in roped off squares. The fighter’s second and bottle holder helped elect which corner to fight from in order to gain the advantage of sunlight or wind. The seconds then chose two umpires, who in turn selected a referee. The ring would have been a crowded space. In the center of the ring were the scratch lines. The boxers came up to scratch and they fought until one was knocked to the ground. The fighter then had 30 seconds to get back to the scratch line for the next round. There were no finite number of rounds and the fight went on until one could not come up to scratch or “threw up the sponge” to concede. The fight purse was made entirely of wager money. If daylight began to fail, the referee would name a time and place for a continuation.

Growing Popularity

As the sport grew in popularity, great fighters became famous. Tom Cribb is memorialised as a modern day pub in London. William Poole as “Butcher Bill” in the movie Gangs of New York. American pugilists James J. Corbett, Jake Kilrain and Yankee Sullivan, as well as Irish champion Dan Donnelly, have all been subjects of best-selling biographies. Boxing was, and still is, a leveler of men. Any man, no matter his ethnicity, can step into the ring and become a legend. Freed slaves Bill Richmond and Tom Molineaux left the USA and became champions in England. Daniel Mendoza, a man of Portuguese Jewish descent became a household name and penned the seminal treatise “The Art of Boxing”. Some names have remained in the collective consciousness so many years later. Names like Jack Slack, which is now the pen name of a well-known, yet anonymous combat sport writer and historian.

Bareknuckle prizefighting had been illegal for decades by the time the Queensberry Rules with 4oz gloves became the only acceptable form of boxing in Britain. With an increasingly effective police force, prizefights were often shut down before they even began. This lead top fighters to leave for the USA, where the bareknuckle prize ring was still in its infancy. Norfolk-born Jem Mace, Champion of England, moved across the Atlantic in 1869 and won the American title too. His style influenced the following two generations of bareknuckle and gloved boxers in the USA, Britain and Australia. The last heavyweight bareknuckle world champion was the “Boston Strong Boy” John L. Sullivan. Sullivan beat Jake Kilrain in 1889 after 75 rounds in the last ever sanctioned London Prize Ring Rules bout.

Modern Resurgence

While bareknuckle survived longer in the US, it eventually faded. Only a small group of enthusiasts continued with unsanctioned fights in warehouses and carparks. The modern resurgence in the UK probably owes more to the underground unlicensed boxing of 1970s London than it does to the 18th and 19th century sport. Fighters like Roy Shaw and Lenny McLean were the big names of the time. McLean, who had a brief acting career before he died in 1998, was recently the subject of the movie The Guv’nor, . That movie also features UFC stalwart Mike Bisping in the role of Roy Shaw. Gypsy bareknuckle has also been simmering away in the background, with legends like Bartley Gorman, “King of the Gypsies”, gaining notoriety throughout his lifetime.

Occasionally fights are held in a ring made of bales of hay and in the early days of the modern bareknuckle bouts, they were held outside in roped off rings. British fighters have begun taking on American fighters in the first ‘international bareknuckle bouts’ in almost 150 years. Increasingly, these fights have taken place in a boxing ring, with ring girls and everything you would expect from a boxing fight night. The difference is, because it’s an unsanctioned show, the fighters are mostly keen amateurs. They are not the well-trained boxers who command big purses and TV deals. They are brawlers; hard men who want to fight and challenge themselves against like-minded men. Men much like the early prizefighters.

Moving Forward

In some regards, the sport does have a connection to the days of Figg and Broughton. It is once again a burgeoning enterprise. A group of people are desperately trying to push it from the fringes into the mainstream. UBBAD promotions, made famous through a 2014 VICE documentary, have re-branded as BKB and are now putting on shows at increasingly large venues to growing crowds and legal wagering. They even held a show at Indigo at the O2, a major UK events venue. Once again, fighters are gaining names for themselves outside of the bareknuckle community and some gyms are training bareknuckle boxers to be more technical.

Figg brought the sport out of the village fairs and into fighting schools. Broughton got it rules and put it in an arena. Later organizations refined the rules and tried to institutionalise the sport. Modern bareknuckle almost feels like it is going through the same transition. Might we see a transition to 4oz MMA gloves for some promotions in the future?